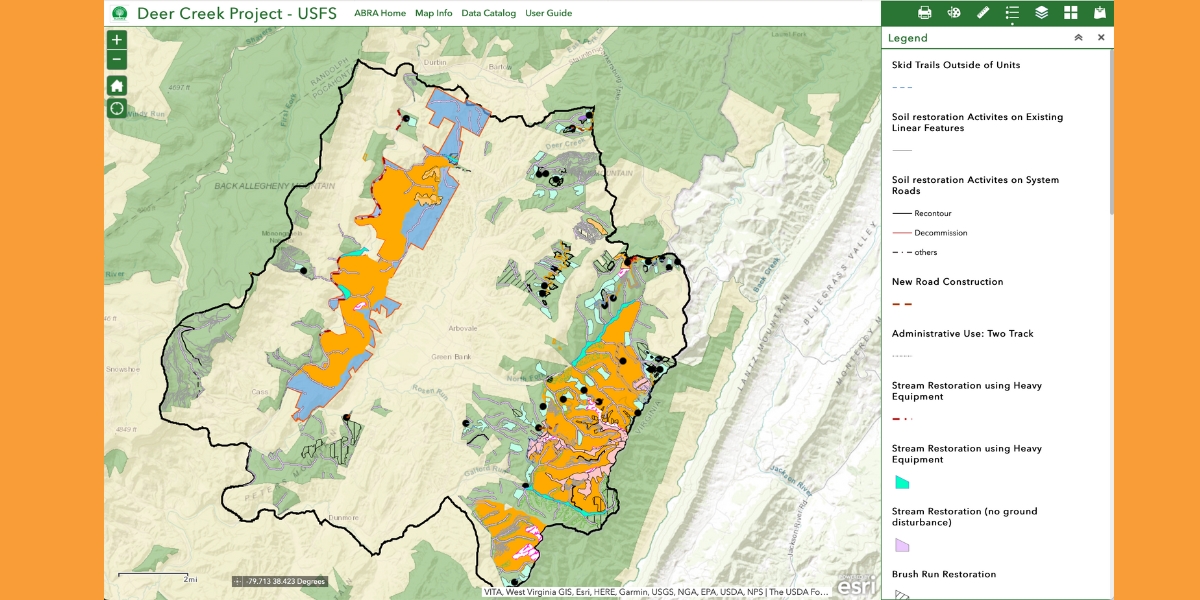

(USFS Deer Creek Project Map by the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance)

By John McFerrin

On behalf of itself and Greenbrier Watershed Association, Center for Biological Diversity, Christians for the Mountains, and Friends of Blackwater, the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy has submitted comments on the proposed Draft Environmental Assessment (DEA) for the Deer Creek Integrated Resource (DCIRP) project in the Monongahela National Forest (MNF) Greenbrier Ranger District.

What the Forest Service wants to do

The proposed Deer Creek Integrated Resources project covers 89,050 acres between Cass and Bartow. It is centered on the town of Green Bank, West Virginia, and contains Deer Creek, Greenbrier River, and a portion of Sitlington Creek headwaters.

The problem, as the Forest Service sees it, is that this area was timbered in the early part of the 20th Century. The timbering and the wildfires that followed meant that tree growth had to pretty much start from scratch. Now the area has been largely left alone for much of the last century. This has resulted in what the Forest Service calls an “even-aged forest” of trees about the same age. The Forest Service thinks this type of forest is not as resilient as it could be. It wants to use some combination of “prescribed fire, commercial and non-commercial vegetation management, herbicide application, tree planting, soil restoration activities, and stream restoration activities” to change this. The term “commercial and non-commercial vegetation management” is a euphemism for timbering.

Procedure and where we are (this part is pretty nerdy and dull; if you skip to the next section, life will still go on)

Before it makes any decisions about the Monongahela National Forest, the United States Forest Service has to consider the environmental impact of what they plan to do. It can’t, of course, do a full environmental assessment of every single thing it does. Some things have a trivial impact and warrant no full assessment. Others have a significant impact and warrant a full assessment.

There is a process for deciding which projects get a cursory look at the environmental impacts, how to reduce them, and which one gets a thorough review.

That is where we are now. The Forest Service has taken a look at the project. Based on that look, it is deciding whether to do a full assessment. It may decide that the project will not have a significant environmental impact. Full speed ahead. If it decides that the project will have a significant environmental impact, it will undertake a full environmental review. By their comments the groups hope to move that decision toward a full review.

The Forest Service could also decide, based on the limited review it has made so far, that the project is too destructive to the environment to continue. That is the result that the groups would prefer.

What groups say is wrong with the proposed project and the study so far

The project doesn’t protect old growth forests

In April 2022, President Biden issued an Executive Order recognizing the value of old growth forests and making their protection and expansion a policy goal. Since then, the Forest Service has publicly recognized the role of forests on federal lands for their role in contributing to nature-based climate solutions by storing large amounts of carbon and increasing biodiversity, mitigating wildfire risks, enhancing climate resilience, enabling subsistence and cultural uses, providing outdoor recreational opportunities, and promoting sustainable local economic development.

The project proposes to cut timber on 1,801 acres. Of these acres, (100%) are in stands at least 60 years old, 288 acres (16%) are in stands at least 120 years old, and some acres within the harvest areas are suspected to be in stands established more than 150 years ago. This is inconsistent with a policy to protect and expand old growth area to cut down stands that either have now or are approaching old growth status.

Doesn’t do anything to mitigate climate change

It is a well-known scientific fact that the forests of the type found in West Virginia act as carbon sinks, absorbing the carbon dioxide that is driving climate change. The February 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report recognized this. The forests cannot continue their role in mitigating climate change if they are cut down.

Contained within the argument that the project does not do anything to mitigate climate change is the observation that the Forest Service has not done what is necessary to reach any conclusion about the effects of the project on climate change. The National Environmental Policy Act requires that the Forest Service take a hard look at the climate change results of its decisions. So far it has not done that.

The groups dismissed the Forest Service’s argument that it didn’t matter that we cut down trees and release carbon. They will grow back. What the argument misses is that the forest will not grow back for a century. During that century, the climate change mitigation will be missed.

The analysis, to this point, has been inadequate

Much of the law surrounding environmental decision-making revolves around the idea of a “hard look.” Regulators—in this case the Forest Service—are allowed to make unwise decisions. They are just not allowed to make decisions based inignorance. They must act only after taking what the law calls a “hard look” at the results of their actions. Before the Forest Service may act, it has to gather the relevant data and seriously consider (the “hard look”) all the information and implications of its actions.

Here, there are several things that the groups commenting think the Forest Service did not take a hard look at.

Within the area covered by this project are one of West Virginia’s largest roadless areas. These are areas which have been identified as having no roads. By virtue of having no roads, they are inherently protected because the lack of roads means that there will be fewer people, fewer people to accidentally start fires, accidentally bring in invasive species, etc. The proposal has not adequately considered the effect it would have on roadless areas.

Completion of the project will inevitably have some impact on water quality. Since this is the case, it would only beprudent to collect information on the current condition of the streams. While there is some data, there is not enough to form a complete picture of what stream quality is like now. The project also contemplates some measures to mitigate damage to water quality. It is not clear from available material that the measures are adequate.

Many streams in the project area are home to Brook Trout and the endangered Candy Darter. The timbering will take place in what appears to be the habit of the Northern Flying Squirrel. Streams in the area have already been degradedbecause of past activities. Before allowing more degradation in this project, we should consider the impact that this project would have on these fish species. The Northern Flying Squirrel has—in the view of the Fish and Wildlife Service—come back from the brink of extinction and is no longer considered an endangered species. The Forest Service has special protocols to protect it and aid in its continued comeback. These protocols were not followed here.

Beyond the impacts on old growth forests, climate change, and things not sufficiently considered (the “hard look”) there lies a fundamental question: is there a need for this project? The groups do not believe that a sufficient need for the project has been established.

Finally, the groups call for a consideration of all alternatives, including the alternative of not doing anything. The point of environmental review is to consider all the environmental consequences and then pick the best course of action. To be an honest consideration it must include doing nothing, something which might be the best course of action. The groups do not believe that the Forest Service has weighed all possible courses of action, including doing nothing.