By Rick Webb and Andrew Young

These photos, dated February 6, 2024, show new logging roads in the North Fork of Cherry River watershed in the Monongahela National Forest. The photos were pseudonymously provided to us on September 25, 2024, along with a message expressing alarm about the lack of project planning and oversight.

(Carelessly constructed logging roads in the Gauley Healthy Forest Restoration project area of the Monongahela National Forest. Streams in this area of the Forest support the endangered candy darter and other species that are sensitive to sedimentation, including native brook trout and the eastern hellbender.)

Despite the misleading name, the Gauley Healthy Forest Restoration (GHFR) project is primarily a timber project. It involves about 3,000 acres of timber harvest and about 60 miles of road construction for heavy equipment access and log transport. Several hundred acres of the timber harvest will be clear cuts, or “regeneration cuts” in today’s Forest Service terminology.

In conducting its environmental review for the GHFR project, the Forest Service relied on a so-called categorical exclusion (CE) as a basis for not preparing an Environmental Assessment and for limiting public participation in the review process. The CE option is a provision of the Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA) of 2003, a controversial law that was seemingly intended to limit review of timber projects on federal lands. The GHFR project, however, fails to meet even the lax requirements of the HFRA.

(February 7, 2024 photo (left) showing logging road and intercepted ground water. September 26, 2024 photo (right) showing the same location.)

Multiple conservation groups have argued that the GHFR project does not qualify for use of a CE, and that a proper National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review, with full and open public involvement, is required. In comments submitted to the Forest Service in 2021, the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy argued that the project does not meet specific requirements for use of a CE, including:

- The HFRA requirement that a project “maximizes the retention of old growth and large trees, as appropriate for the forest type, to the extent that the trees promote stands that are resilient to insects and disease; considers the best available scientific information to maintain or restore the ecological integrity, including maintaining or restoring structure, function, composition, and connectivity…” (FSH 1909.15_32.3; HFRA, Section 603(b)(1)(A)). — The Forest Service does not explain how its proposed clear cuts maximize retention of old trees or how clearcutting would maintain or restore ecological integrity.

- The HFRA requirement that projects must be designed “to reduce the risk or extent of, or increase the resilience to, insect or disease infestation in the areas” (FSH 1909.15_32.3; HFRA, Sections 602(d) and 603(a)). — The project is clearly not about disease and insect control. As indicated in documents obtained through FOIA requests, the project area does not have enough insect and disease activity to develop units aimed specifically at treating insect and disease problems.

- The requirement in NEPA’s implementing regulations that prohibits breaking a connected action into small parts in order to meet the definition of a categorical exclusion and avoid the appearance of significance of the total action (38 CFR 200.3(b)(1)(A)). — The project is an improper segmentation of the Forest Service vegetation management program in the project area. The GHFR project area is contained within the larger project area of the Cranberry-Spring Creek project. Both projects propose very similar vegetation management activities in the same area at the same time.

The Conservancy’s 2021 comments on the GHFR also raised other important issues. As revealed through FOIA requests, multiple Forest Service scientists raised concerns about project impacts during the review process that were removed from final reports or otherwise dismissed without explanation. These included concerns about:

- Long term substantial adverse impacts to watershed hydrology

- Long term substantial impacts to soil properties and productivity

- Impacts to values associated with Wild & Scenic Rivers status

- Lack of rationale for concluding that the project will not harm aquatic life

- Failure to analyze impacts to critical habitat of the endangered candy darter

Concerns about the endangered candy darter are particularly significant, given the critical importance of the North Fork of the Cherry River and the Cranberry River to the somewhat dim prospects for continuation of the species. It’s not an overstatement to argue that survival of the candy darter is dependent on National Forest management.

The Forest Service is currently proposing or implementing multiple major timber harvest projects in the Monongahela National Forest that have potential to impact the candy darter (GHFR, Upper Greenbrier North, Greenbrier Southeast, Cranberry-Spring Creek, Deer Creek, Sitlington Creek, and maybe others). Additionally, activities on private land are impacting candy darter habitat.

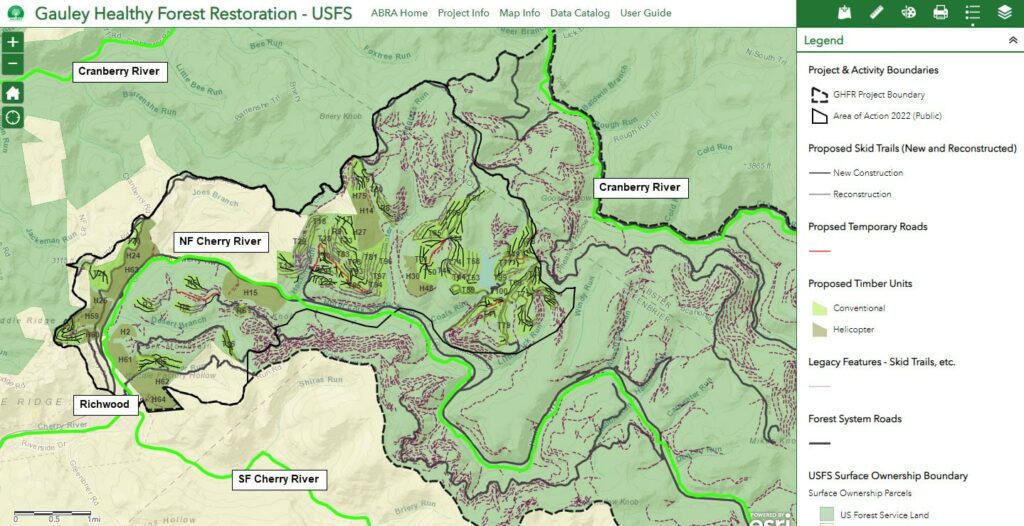

(The main GHFR project area, showing proposed timber units and road construction, old logging roads (legacy features), and designated critical habitat for the endangered candy darter (bright green stream lines). The February 6, 2024 logging road photos were obtained at the western-most extent of the project. This map, with additional project-related layers and access to project review documents, is online at the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance website.)

The Conservancy’s 2021 comments on the GHFR objected to the general lack of attention given to the candy darter, stating:

Analyses that have been completed to date have not included a thorough investigation of baseline conditions, existing impacts, or potential impacts of projects that are in the planning stage. All of the Forest Service analyses to date have relied on Best Management Practices and unsupported assertions to reach conclusions of “not likely to adversely affect,” without providing any data, evidence, or reasoned rationale to support the effectiveness of BMPs and the conclusions regarding effects on the candy darter. Each of these projects, including GHFR, should be analyzed using real-world data on the likelihood of short-term and long-term sediment production, soil base cation depletion, hydrologic disruption, and the impacts such perturbations are likely to have on candy darter populations. Finally, the Forest Service should conduct an analysis of the cumulative impacts of all of these public and private land activities on the long term viability of the candy darter.

To date, however, it’s hard to identify any meaningful change in Monongahela National Forest management practice that has occurred in response to endangered species designation for the candy darter. Business as usual does not bode well for this disappearing species. The Conservancy continues to advocate for forest management focused on watershed and ecosystem integrity, and we are engaged in review of multiple Monongahela National Forest projects. We are also engaged in a legal challenge to the Greenbrier Southeast project due to Forest Service failure to properly assess the environmental baseline before approving the project.

Concerning the GHFR, the Conservancy has resorted to FOIA requests and a lawsuit to obtain access to critical project information and plans. The Conservancy currently has a petition in federal court, asking the court to require the Forest Service to provide implementation plans for the project. With additional FOIA requests, we are seeking access to project status reports, timber unit and road inspection reports, and timber and construction contracts. We are also seeking environmental survey and monitoring data, including water, soil, and aquatic life and habitat.