By Patricia Gundrum

Spotted lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) are native to China and other regions of Asia. First detected in Berks County, Pennsylvania, in 2014, they have managed to spread within a decade to most of the counties in Pennsylvania and Maryland. All counties of New Jersey have reported the presence of spotted lanternflies. New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, several counties in Ohio, Indiana, Virginia, North Carolina, one in Michigan, and seven in the eastern and northern panhandle area of West Virginia have all reported sightings of the insect.

Despite their rather rapid dispersal, the adult insect is not a particularly good flyer and can only fly short distances. The immature nymphs cannot fly but are powerful jumpers. So, how did they manage to move so far? Human transport! Egg masses laid on surfaces moved to new locations, and adults and nymphs hitchhiking on vehicles are the prime reason for their spread.

The spotted lanternfly is not a fly. The insects are planthoppers in the order Hemiptera. This order contains insects with stylet-type mouthparts that pierce and ingest liquid sugars from a plant’s vascular phloem cells. Among the other more common Hemiptera are stink bugs, aphids, cicadas, hemlock woolly adelgids and leafhoppers.

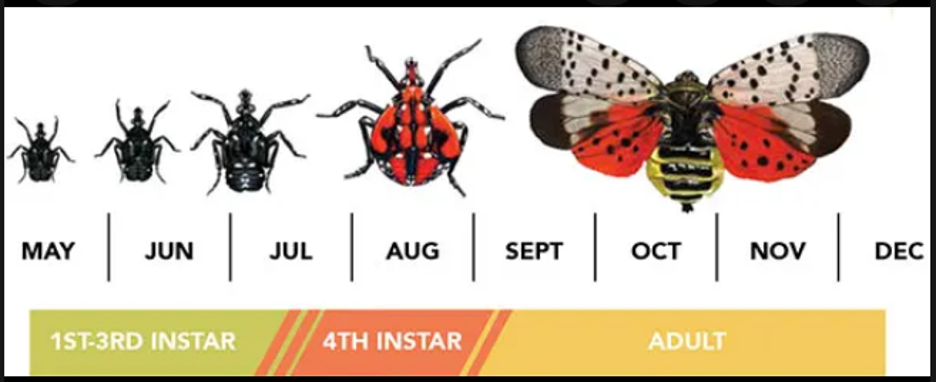

The spotted lanternfly produces one generation per year. The life cycle begins with the egg stage. Egg masses are deposited in one-inch-long segmented rows containing up to 50 eggs. The masses look like grey mud and are difficult to detect—the female deposits egg masses from September through November, depending on the first killing freeze. The nymphs emerge from the eggs in late April to May.

There are four stages of nymphal development, referred to as instars. The first three instars are black with white spots. Their long, powerful jumping legs are rather distinctive. Each instar increases in size. By the fourth instar, the nymphs are larger—approximately 3/4 inch-and bright red with black spots with long jumping legs. The fourth instar is active now—from July through August. However, these stages may overlap with the flying adult stage appearing as early as July and extending through December. The adult is rather colorful with gray polka-dotted forewings and red and black striped and dotted hind wings. The abdomen is yellow.

All life stages (nymphs and adults) feed on plant tissue, “sucking” the sugary sap from the phloem tissue with their stylet mouthpart. The first three instars do not have stylets that are strong enough to penetrate woody tissue, so they will only feed on succulent growth. The fourth instar nymphs and adults can penetrate woody tissue and have a broad host range. However, the fourth instar and adult stage have certain preferences. The tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is the preferred host plant for feeding and egg-laying.

Since the tree of heaven is considered a noxious, invasive weed tree, why should it matter if they feed on this plant? For one, this host plant is crucial in the spotted lanternfly’s development and preference for egg-laying. However, the tree of heaven’s reduced sap flow later in the season will initiate movement to other host plants to obtain other plant sap sources. The other host plants include grapes, hops, maple, and black walnut, with an assortment of additional “secondary” hosts. The spotted lanternfly is known to feed on over 70 host plant species!

Fortunately, spotted lanternfly is not likely to actually kill host trees. Some stylet feeders are known vectors of plant diseases, but the spotted lanternfly is not. The primary impact of the insect feeding is the prodigious amount of sticky substance known as honeydew which is excreted through their ingestion of plant sap. The sticky honeydew is a prime substrate for black sooty mold fungi growth. The black mold can cover the leaf surfaces, thereby reducing the ability of the plant to photosynthesize. Honeydew can also land on surfaces underneath trees, such as picnic tables, creating a big mess! Bees, wasps, and other insects are also naturally attracted to this sugary substance.

The grape vineyards are most severely and economically impacted by the spotted lanternfly. Exclusion netting over the grape rows has been shown to reduce spotted lanternfly populations by 99.8 percent (Penn State University extension data).

Recommendations for the public include:

- Scraping off and destroying the difficult-to-detect egg masses.

- Squashing all life stages of spotted lanternflies.

- Inspecting shoes and vehicles when traveling to and from infested areas.

Cover photo from the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources.