By Andrew Young

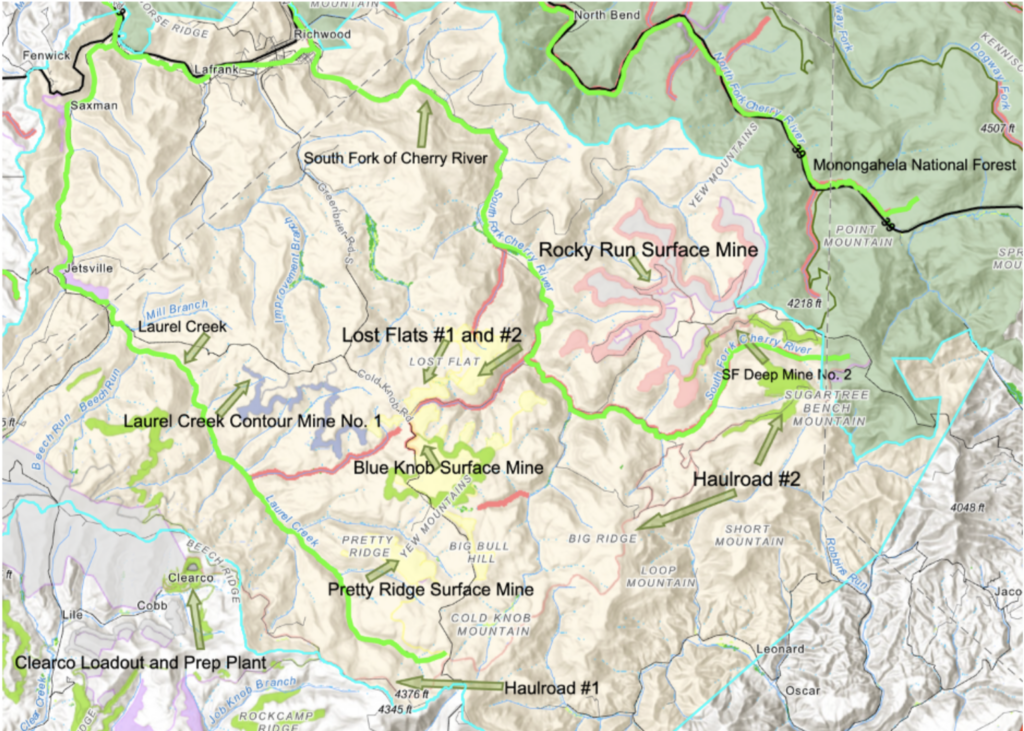

Part one in this series provided a brief overview of the harmful impacts that a handful of strip mines and coal haul roads operated by one company, South Fork Coal Company, are wreaking in the Laurel Creek and South Fork of the Cherry River–watersheds that are designated occupied critical habitat for the most important remaining metapopulation of candy darters.

In a brazenly corrupt way that harkens back to the darkest King Coal days, this devious company appears to be implicated in a conspiracy along with the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP), the West Virginia Field Office of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement (OSMRE), to dishonestly evade regulation under the 2020 Programmatic Biological Opinion (2020 BiOp) by having all parties play ignorant about the presence and potential impacts upon the candy darter and its listed critical habitat, while still claiming “take coverage” benefits under the same 2020 BiOp.

Part two will delve into two of the important laws at play here that exist to protect our region’s treasured biodiversity: the Endangered Species Act and the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act.

Essentially, South Fork Coal Co. and the agencies are trying to get the benefit of the BiOp to protect themselves from liability, while avoiding the required additional species impact analysis and other layers of protection that are required to actually avail themselves to legitimate take coverage under the 2020 BiOp. It is a scheme that completely lacks professionalism and self-respect by those who have participated in it, and we, the Conservancy, and coalition partners, are going to hold each and every single conspirator to account for it. But to delve into the specific violations (in part three of this series), an overview of the Endangered Species Act and the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act provisions is needed.

Map of South Fork Coal Company operations that impact candy darter critical habitat. Impaired streams are shown in red, critical habitat shown in lime green. (Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance’s Coal Operations in Candy Darter Habitat Conservation Hub Site)

The Endangered Species Act

The central purpose of the Endangered Species Act is to protect endangered and threatened species and the ecosystems upon which they depend. The Supreme Court has declared that the Endangered Species Act “represent[s] the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species ever enacted…” As the Court recognized, “Congress intended endangered species be afforded the highest of priorities” in order “to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost.” To that end, the Endangered Species Act provides a program for conserving endangered and threatened species and the ecosystems upon which they depend.

Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act requires all federal agencies to work to recover listed species, and it contains both a procedural and a substantive requirement toward that purpose. Substantively, it requires federal agencies to ensure that any action authorized, funded, or carried out is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any threatened or endangered species or adversely modify the species’ critical habitat. To avoid jeopardy or adverse modification of critical habitat, Section 7(a)(2) sets forth a procedural requirement that directs an agency proposing an action (“action agency,” here the OSMRE granting Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act permits) to consult with an expert agency (the Fish and Wildlife Service here) in order to evaluate the effects of the proposed action on listed species.

It is illegal to engage in any activity that “takes” an endangered species absent valid take coverage under Endangered Species Act Sections 7 or 10. Persons subject to the take prohibition include individuals and corporations, as well as “any officer, employee, agent, department, or instrumentality of the Federal Government…[or] any State.” Further, “[t]he Endangered Species Act prohibitions apply to actions by state agencies where their regulatory programs approve actions by third parties that contribute to causing take.”

If, during Section 7 consultation, the Fish and Wildlife Service determines that the action is not likely to jeopardize a species, it may issue an incidental take statement. The incidental take statement must specify the impact of such incidental taking on the species, set forth “reasonable and prudent measures” that the Fish and Wildlife Service considers necessary to minimize such impact, and include the “terms and conditions” that the action agency must comply with to implement those measures.

When the terms and conditions of the incidental take statement and the biological opinion are adhered to, the incidental take statement provides “safe harbor” for the action agency, state regulators, and permittees (South Fork Coal Co. here), authorizing limited take of listed species that would otherwise violate Section 9’s take prohibition. However, if the terms and conditions of a biological opinion and incidental take statement are violated, agencies and private actors are exposed to take liability.

The Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act and the Endangered Species Act

The Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement (OSMRE) within the Department of the Interior is the primary regulator of coal mining under the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act unless and until a state demonstrates that it has developed a regulatory program that meets all of the requirements of the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act and the implementing regulations issued by OSMRE.

West Virginia has received the authority from OSMRE to be the primary regulator within the boundaries of the state. However, even after a Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act program has been delegated to a state, OSMRE retains oversight of that program through supervision of the state’s implementation of the regulatory program. OSMRE further maintains federal oversight over state Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act programs by funding them on an ongoing basis. The Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act specifically requires that OSMRE evaluate and oversee the administration of approved state programs, and requires that OSMRE enforce the terms of the statute and substitute its enforcement power for that of the state–or take back implementation authority from the state–should it find that the state has failed to adequately enforce its state-delegated Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act program.

OSMRE therefore retains discretion and control over the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act program, even where the program has been delegated to a state authority, as here. This includes oversight and enforcement of the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act provisions regarding protected species.

The 2020 BiOp ostensibly provides Section 7 coverage for all listed species, and designated or proposed critical habitat, potentially affected by surface coal mining, surface effects of underground coal mining, and coal mine reclamation, nationwide. Specifically, it provides Section 7 coverage for OSMRE’s implementation of Title V of Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act, including where states have primacy under the statute, as in West Virginia. In the 2020 BiOp, the Fish and Wildlife Service concludes that OSMRE’s implementation of Title V of Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act “is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of proposed or listed species and or destroy or adversely modify designated or proposed critical habitat.”

To reach this conclusion, the Fish and Wildlife Service explicitly relied upon: 1) the coordination process between the states and Fish and Wildlife Service that ensures the creation of adequate protection and enhancement plans and species-specific protective measures and 2) OSMRE’s oversight of state programs and enforcement of the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act in states with primacy, including the proper implementation of protection and enhancement plans and their species-specific protective measures. It is only through compliance with the terms and conditions of the 2020 BiOp that OSMRE, and through it the states and mine operators, receive coverage via Section 7.

The 2020 BiOp requires that the states initiate “coordination” with the Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure that adequate protection and enhancement plans and species-specific protective measures are in place to avoid harm to listed species and their critical habitat. As early as possible in the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act permitting process where the proposed action may affect listed or proposed species or designated or proposed critical habitat, the state must submit a proposed protection and enhancement plan to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The Fish and Wildlife Service then works with the state through a “technical assistance process” whereby the Fish and Wildlife Service ensures that the protection plans, and species-specific protective measures are adequately protective to avoid jeopardy and adverse modification. States must also reinitiate coordination with the Fish and Wildlife Service upon the newly proposed or final listing or designation of potentially affected species or critical habitat under the Endangered Species Act.

That’s it for part two, the specific Endangered Species Act and Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act violations will be expanded upon in part three.

View the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance’s interactive map and Hub site documenting the expansion of surface mining and timbering in critical candy darter habitat.

Cover Image: Rocky Run Surface Mine visible in the foreground with Point Mountain and Sugartree Bench Mountain in the background. Cranberry lies just beyond the two mountains. (Photo courtesy Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance Pipeline Airforce)