By Andrew Young

Situated just southeast of Richwood, West Virginia, near Cranberry, the Laurel Creek and South Fork of the Cherry River watersheds harbor outstanding ecological character and tremendous beauty. They also provide some of the best remaining habitat for numerous species of concern, most significantly, the stronghold Upper Gauley metapopulation of the critically endangered candy darter—a beloved native Appalachian fish.

The two watersheds are still remarkably wild and remote, even after 100-plus years of encroaching destructive impacts from the surrounding timber and coal mining industries. These watersheds are breathtaking—anybody who has fished, kayaked, walked or spent time here will concur.

Amid the climate emergency and accompanying sixth mass extinction event, our time to act is dwindling, and the protection and recovery of these watersheds is more urgent than ever. Put simply, conserving these lands and waters for future generations through preserving the physical characteristics that support this rare biodiversity depends upon responsible and transparent decision-making by regulators, coal and timber operators, and meaningful, informed public involvement.

Unfortunately, instead of tight planning, staunch enforcement, and hawkish oversight by regulatory agencies, one coal company, South Fork Coal Company, owned by White Forest Resources (headquartered in Knoxville, Tennessee, through its wholly owned subsidiary Xinergy Corp. and its subsidiaries) has been strip mining, deep mining, and coal hauling with reckless abandon and disregard in this sensitive ecosystem. While South Fork Coal Company pursues dirty money and contributes immense downstream greenhouse gas emissions from their metallurgical coal (used for the steelmaking process, which is between 8-10 percent of global greenhouse gasses emitted), our state and federal agencies have been lax in their oversight and enforcement duties.

This quagmire represents a grand failure of our environmental safeguards, with weak regulators held captive by rogue coal operators. As a result, our waters, rare Appalachian species, and public lands are paying the cost. The time to act is now, or it may be too late for the candy darter. Extinction is forever, but we have the ability and the means to stop it if we can muster the will.

This issue must be framed by two guiding ideals. First, the area at issue is entirely within the proclamation boundary of the Monongahela National Forest. The proclamation boundary for a national forest is the area proclaimed by federal law—here that occurred on April 28, 1920, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the original 1.7 million-acre proclamation boundary establishing Monongahela National Forest. And second, these watersheds are designated critical habitat for the most important metapopulation of the candy darter. Despite this, the Endangered Species Act requirements under the 2020 Programmatic Biological Opinion are not being complied with at any relevant Surface Mining Control Reclamation Act (SMCRA) permitted facilities.

To the first, although the timber company Weyerhaeuser swooped in to take the land and negotiate its mineral leasing rights to South Fork Coal Company before the Forest Service could, the American People are the rightful owners of these lands and waters. This sacred place is ours, and we want it back.

Were the land at issue to be national forest, as it rightfully should be, it would be off limits to mining location, and obtaining a mining lease would be burdensome, likely to the point of impossibility. This is because the General Mining Law only applies to “public domain” lands, or lands the federal government has held since they became part of the United States.

Mining claims are not permitted on “acquired lands”—lands that were transferred to private ownership and then reacquired by the United States—although these lands may technically be available for leasing under the Acquired Lands Act of 1947. Virtually all of the Eastern National Forests are acquired lands.

Even if the lands here were to be theoretically open to mine leasing, a federal government agency (the Forest Service) would be exercising a discretionary action in deciding any lease to coal mining operations. It thus would be subject to rigorous National Environmental Policy Act procedural requirements, substantive formal Section 7 consultation requirements under the Endangered Species Act, and strict requirements under the Clean Water Act.

The product of this “hard look” under the National Environmental Policy Act, as well as the Endangered Species Act BiOp and Incidental Take Statement, and Clean Water Act permits, would be ripe for challenge in federal court if they were inadequate. These permitting hurdles would likely then look similar to those faced by the Mountain Valley Pipeline and Atlantic Coast Pipeline and no doubt result in immense costs for any potential mine operation(s). Furthermore, a mining lease on federal lands would require royalties paid to the United States Treasury and cut further into the operation’s profit margin.

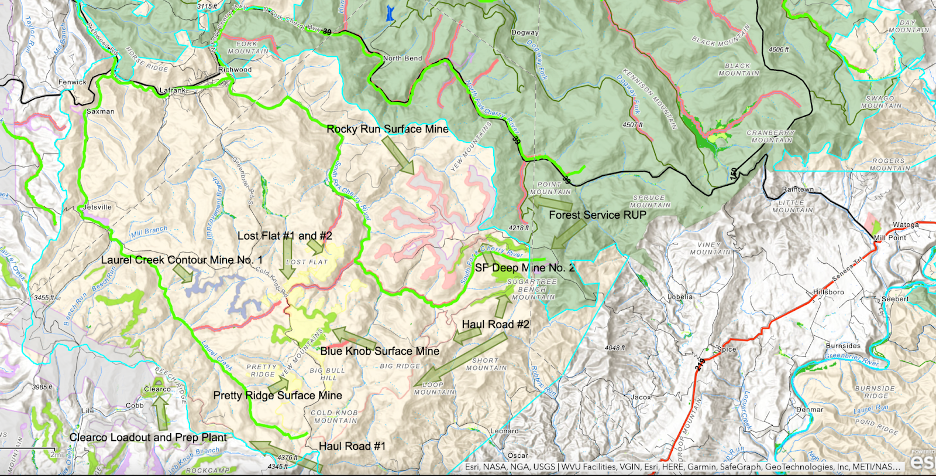

Instead, the land is held by Weyerhaeuser and leased to South Fork Coal Company in order to strip mine and clear-cut lands they should not own. Instead of one federal action agency and land manager (the Forest Service) in charge, there is a patchwork of various state and federal agencies, none of whom are in compliance with the Endangered Species Act or other applicable environmental laws. One specific issue the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy has already highlighted in this area is that the Forest Service has violated the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act by granting South Fork Coal Company a road use permit to cross the Monongahela National Forest from the Rocky Run Surface Mine to the Haul Road #2 without undergoing any National Environmental Policy Act analysis, and without engaging in any Endangered Species Act consultation with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, both of which are required by law.

Without this Forest Service Road Use Permit, the Rocky Run mine could not get the coal to the processing and loadout plant in Clearco, West Virginia.

The Conservancy is part of a coalition that sent the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service a notice of intent to sue on these issues, and a complaint is forthcoming. But that pending lawsuit only touches on the National Forest crossing, as the map below shows, and the Endangered Species Act requirements have been disregarded at every facility named on the map below within the Monongahela National Forest Proclamation Boundary.

And to the second issue, the Conservancy is now working with partners to hold the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement accountable for having systematically violated the Endangered Species Act by failing to oversee and force the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection’s compliance with the 2020 SMCRA Programmatic Biological Opinion (2020 BiOp) requirements that:

a) the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection provide a draft Protection and Enhancement Plan to the Fish and Wildlife Service early in the permitting process for SMCRA facilities with species-specific protective measures to protect the candy darter from jeopardy and adverse modification of critical habitat, and minimize incidental take during active mining and post mining reclamation;

b) that the Fish and Wildlife Service ensure all relevant SMCRA facilities have finalized Protection and Enhancement Plans and the species-specific protective measures are sufficiently protective of the candy darter and its critical habitat; and

c) the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation Enforcement oversees West Virginia’s implementation of SMCRA and enforces the requirements of the statute when the State has failed to do so, including the requirement that SMCRA facilities that drain to candy darter habitat have adequate Protection and Enhancement Plans in place.

South Fork Coal Company has a track record of rampant non-compliance with the water protection requirements of SMCRA and the Clean Water Act across all of its permitted facilities in the South Fork Cherry River and Laurel Creek watersheds.

Most recently, South Fork Coal Company was issued a Notice of Violation for spreading raw coal, a toxic pollutant, across the surface of Haul Road #2 that drains to candy darter critical habitat (see map above).

The manifest harm that the candy darter has suffered due to coal industry pollution underscores the need for the mine operator, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, OSMRE, and the Fish and Wildlife Service to fashion and effectively implement appropriate protective measures.

At this time, however, 30 months after the issuance of the 2020 BiOp, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection has taken no action to initiate the process of developing Protection and Enhancement Plans for the candy darter and its designated critical habitat for any SMCRA permitted operation affecting the species in either of these two watersheds.

This is both surprising and unacceptable because South Fork Coal Company is the only coal company operating in candy darter critical habitat. Yet, none of the company’s relevant SMCRA-permitted facilities have Protection and Enhancement Plans in place for this species, a 2020 BiOp non-compliance rate of 100%.

Stay tuned for part two in this series for a more in-depth discussion of the Endangered Species Act, particularly as related to coal mining activities in designated candy darter critical habitat, and the systematic violations by South Fork Coal Company and regulatory agencies in these two watersheds. For more information, please visit the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance Conservation Hub website called “Coal Operations and Candy Darter Habitat.”

Read part two: King Coal, Don’t You Lose Any Sleep?

Cover photo: (Photo courtesy of the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance Pipeline Airforce: Showing the Rocky Run Surface Mine operation directly adjacent to the Monongahela National Forest. This operation drains directly to designated critical habitat for the endangered candy darter, see map below.)