By Robert Beanblossom, Cradle of Forestry in America

West Virginia faces many serious environmental issues. Water pollution, strip mining, threats to public lands, air pollution, forever chemicals and many others clamor for our concern and attention. However, overriding all others is climate change.

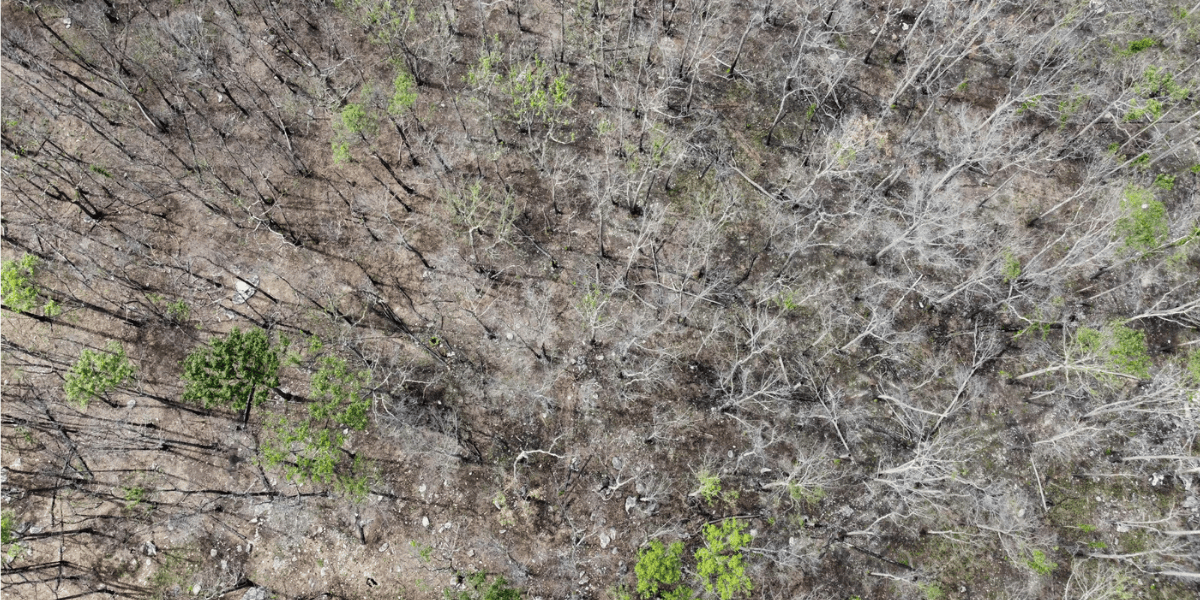

It is paradoxical and unfortunate, however, that one of the most harmful and destructive threats has been overlooked, particularly now when that very threat is increased by a rapidly changing climate. I am speaking of the danger posed by wildfires.

The responsibility for protecting the forests of West Virginia has been relegated to the Division of Forestry but the agency has always been underfunded. Due to this, it is unable to meet expected mandates and is only able to perform what is little more than a token effort.

Why is the Division of Forestry so poorly equipped to cope with the problem in an era when wildfire control in the rest of the nation has become highly sophisticated and mechanized? Why is it that when I left that agency close to fifty years ago because I grew tired of having nothing to work with, it has even less today?

The simple answer for this enigma is the lack of political will to assign priority to wildfire control commensurate with the destructive impact which uncontrolled wildfires have on our environment. But it is a far more complex issue and one that has been created over time by the influence of coal on our socioeconomic and political structure.

Although forests throughout West Virginia are vulnerable to wildfires, the problem has historically been confined to southern West Virginia and developed there largely for the following reasons.

About the turn of the 20th century, land was cheaply acquired by out-of-state coal and land companies. These large companies were only interested in and focused solely on extracting their mineral wealth and cared little for what happened to the surface. Over the years, they have made only minimal efforts to prevent wildfires because they knew their profits were safely tucked underground. Dependence on coal company leases diminished locals’ incentive to protect the land. Having no direct ownership of the land resulted in a lack of a “land ethic” developing among the residents of southern West Virginia.

Along with a lack of appreciation for the land, there is widespread poverty, high dropout rates and high unemployment. All of which indirectly contributes to the wildfire problem because if people fail to acquire fundamental educational skills, it is impossible for them to assimilate scientific concepts about forest management and fire protection. Not only does this phenomenon manifest itself in environmental problems, but it carries over into other aspects of daily life and is no doubt a contributing factor in the widespread, chronic drug problems that exist today in southern West Virginia.

The coal industry has always been characterized by a hostile “us against them” mentality. One of the best examples of the callousness and indifference on the part of the coal industry was the Buffalo Creek disaster. Feb. 26, 1972, a poorly constructed and maintained coal slurry dam in Logan County gave way killing 125 individuals, many of them women and children, and destroying over a thousand homes. Pittston Coal Corporation, who owned the make-shift dam, was quick to declare it “an act of God.”

Thousands of miners have either been killed or maimed in mining accidents. Each one was a result of a violation of federal or state health and safety law by these companies. Many more suffer from black lung disease. In no other industry is the division of management and labor so great, and this attitude carried over into the realm of land management.

The prevailing attitude of the local population has been, “It’s the coal company’s property, let them worry about it.” Striking back at these companies by deliberately setting wildfires was a frequent practice.

Religion has also been a strong contributor to perpetuating many of the social and economic ills in Appalachia, especially southern West Virginia. Strict fundamentalist religion perpetuated the concept of fatalism and instilled the belief that one cannot change their lot in life, especially in rural illiterate mountaineers. This attitude was first introduced by company paid ministers at the beginning of the 20th century to quell union organizers and has been carried forward ever since.

Because of this unique land ownership pattern, there has been no catalyst for change in southern West Virginia. There is no middle class to push for and institute reforms to bring about positive incremental changes in social norms. This has manifested itself in two ways.

First, it is widely believed that the landowning class has often been responsible for social and historical changes taking place in any given area. Naturally, with large absentee landownerships that opportunity never existed in southern West Virginia.

Second, what middle class there is – store owners, professionals, etc. – seem to be quite content to maintain things as they exist. In Harry Caudill’s book, Watches of the Night, Caudill lamented upon this fact in east Kentucky. He stated of teachers, “Many locals went away to colleges located for the most part in the Appalachian plateau and learned to teach little more than the status quo.”

Our political system is also a result of this situation of landownership patterns and coal company dominance and remains committed to maintaining the status quo. Political corruption is quite common; with Mingo County being the latest example.

The county commissioner, the county judge and other officials were sentenced to prison for various crimes just a few years ago. It will be just a matter of time before federal prosecutors’ step in again to bust another corrupt political machine. In years past it has happened in Logan County, Lincoln County and other places. No doubt it will happen once again somewhere in southern West Virginia.

Therefore, the Division of Forestry has always struggled due to this lack of interest from residents, large landowners and the political structure at both the state and local level. The Division of Forestry is incapable of handling a catastrophic fire situation especially during extreme drought years because it simply does not possess the power, the equipment or the funding to do so. It is imperative this situation be reversed.

In the past few years at least two lives have been lost due to wildfires. Last year a dozen or so homes were destroyed to say nothing of the environmental consequences. I think many West Virginians are lulled into a false sense of security by watching the response to wildfires in other states. If you think that if there is a large wildfire threatening your home, there will be crews, bulldozers and planes arriving to extinguish it, you are sadly mistaken. At best one or two employees from the Division of Forestry might show up if they are not tied up with other fires and your local volunteer fire department may respond but that is about it. The Division of Forestry has fewer than 100 employees statewide and that includes clerical staff and vacancies.

In recent years, climate change has established a pattern where a normally dry West becomes dryer, and the Eastern portion of the United States has remained near normal in rainfall with pockets of drought occurring. Last summer was exceptionally dry with many wildfires occurring during a time when they normally do not occur, but drought moderated during the critical fall fire season months. However, occurrence and acres burned were well above average.

When prolonged dry conditions do occur, West Virginia could easily face a situation like that in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, in the fall of 2016. On November 23, a wildfire burned 17,900 acres, claimed 14 lives, destroyed 2,640 homes and businesses and caused two billion dollars in damages. Fuel conditions in West Virginia are about the same as east Tennessee. A wildfire the magnitude of Gatlinburg’s could easily happen here.

Governor Morrissey and the Legislature have a clear moral duty to see that the Division of Forestry and its wildfire control program are well financed and our forests, our citizens, and our homes and businesses are protected from catastrophic wildfires.

Robert Beanblossom, a member of the Society of American Foresters, retired after a 42-year career with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources and moved to western North Carolina in 2015 as the volunteer caretaker at the U.S. Forest Service’s Cradle of Forestry in America. He has served on numerous incident management teams battling wildfire throughout the United States. He can be reached at r.beanblossom1862@outlook.com.