By David Elkinton

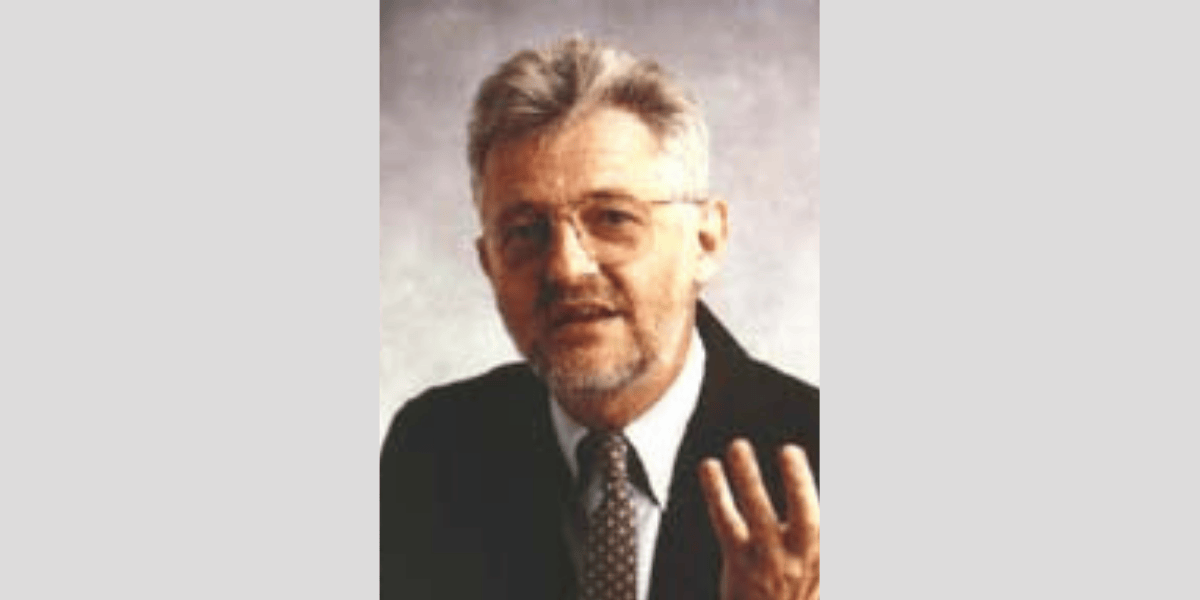

Nicholas Zvegintzov, a former Regional Vice President of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and anti-strip-mining activist, passed away on Jun. 3, 2024, in Staten Island, New York, at age 84.

At a memorial service via Zoom, held on Dec. 7, 2024, a full review of Nick’s life emerged. Educated in England, he studied at Oxford with a pioneer in applied mathematics, the forerunner to computer science.

Nick arrived in the United States as an expert in the field just as it was taking off. I remember him telling me, when I asked what he did in Washington DC during our time together in the Conservancy, that he worked on software at the World Bank. I have since learned that he freelanced with many organizations in the early days of computing. Later, in New York, he founded a software newsletter and served as a technology consultant.

But to the Conservancy members of a certain age, Nick Z, as we knew him, was an outspoken opponent of strip-mining and knew of it first-hand. He had acquired a small house in the community of Duo in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, and often lived there between computer jobs in DC or escaped there to write.

When a strip-mine threatened Duo, he helped organize the community and became active with the Conservancy.

Nick first attended a Conservancy meeting in January 1973, my first as Conservancy president. Over the next seven years, he would write over seventy articles for the Highlands Voice, making him among the most frequent contributors during those years.

The index of the Conservancy history, Fighting to Protect the Highlands, where his name appears last (as it did in virtually every alphabetized listing), lists many references to his Duo activism and his role as the Conservancy’s correspondent in Washington.

In a 1976 Highlands Voice article, Nick captioned himself the “White House correspondent for the Highlands Voice.” In a December 1978 article, he announced a great victory, “On the evening of Nov. 10, without ceremony, President Carter put his signature to the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978, which designated the New River Gorge National River.”

In the Spring of 1980, he resigned as Washington VP and moved to New York, where he remained for the next 44 years.

Over the brief seven years that Nick Z was an active member and officer of the Conservancy, he made a deep impression and shared his life stories with many others over our potluck dinners and annual weekend events.

He made a significant contribution to both his community and the Conservancy. When he moved to New York’s Staten Island, it was our loss, but unsurprisingly, he became an activist there, leading several campaigns for civic improvements that I only learned about at his memorial Zoom. Rest in peace, Nick Z.