By Hugh Rogers

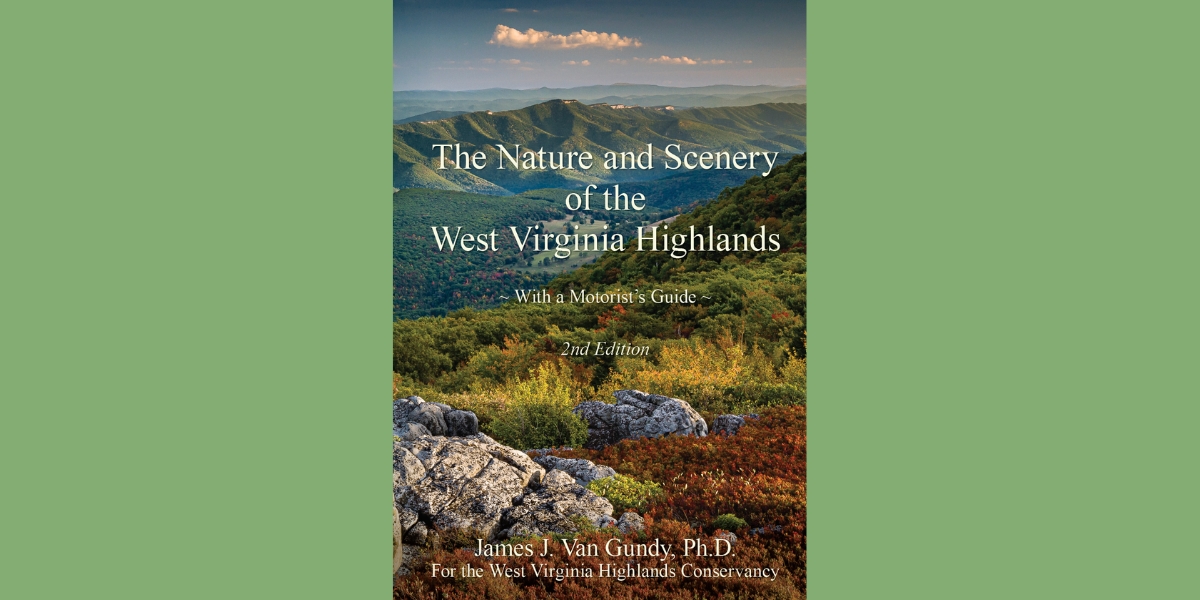

For our members and for all who care for, are intrigued by, and like to explore the highlands, the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy is publishing an expanded second edition of Jim Van Gundy’s brilliant, beautiful guidebook, The Nature and Scenery of the West Virginia Highlands.

This is the ideal companion to our Monongahela National Forest Hiking Guide. The Hiking Guide takes you inside the Forest on foot; Van Gundy’s book tells you how the Highlands came to be the way they are (geology, history), describes them in detail (climates, ecosystems, forests, waters, plants and wildlife), and takes you to and through them on thirty-three highway segments. The latter half of the book, the Motorists Guide, explains the terrain, suggests places to stop, and points out detours worth taking.

When the self-published first edition came out in 2022, Van Gundy said he had first thought of writing it 40 years ago. He taught at Davis and Elkins College, becoming Chair of the Department of Biology and Environmental Science; raised a family, led outings for research and pleasure, and traveled. Not the least of his responsibilities was a stint on the WVHC board. Then Covid struck. Jim had retired, and he recognized the opportunity to write. It was a successful venture—half the print run sold in the first six months. The remainder were gone last year.

Fortunately, questions about the book’s future stirred new conversations. Kent Mason, whose photographs add so much to the Hiking Guide, agreed to donate any Jim would like to use in a new edition. Jim considered several changes he’d imagined after the book came out. When the WVHC board signed on, he went back to work. The result is now in our hands.

Inescapably, the author must begin with his definition of “the Highlands.” Many are possible. Narrowly, we’d leave out everything west of Laurel Mountain, the final ridge of the Allegheny Mountains. (At the latitude of Elkins, I’m showing my bias.) Beyond that is a lumpy plateau.

Van Gundy’s approach to his subject is both wide and deep, so it’s not surprising that his definition is expansive. It does include a portion of the Allegheny Plateau. His boundaries are drawn by the highways: everything “east of I-79 from the Pennsylvania border south to . . . US 19 near Sutton, then to the east of US 19 to Beckley. Then to the east of I-77 between Beckley and the Virginia state line near Bluefield.”

The introduction lays out the topography, introducing several basic terms and concepts with diagrams and illustrative photos. The deeper (millions of years) and wider (global) history are found in Chapter Three. This is fascinating for an old head whose only reading about geology since one college semester was John McPhee’s series, “Annals of the Former World,” in the 1980’s. As with geology, so with history, climate, forests, waters, and the other main topics, Chapter One whets the reader’s appetite for more detailed coverage in the nine following chapters.

For this brief review, I’ll skip between material in Section I and the narratives of road segments in Section II, sharing some tasty bits.

Human history, unsurprisingly, begins and concludes with controversy. The first addresses the permanence or transience of native settlement before European colonization. Van Gundy cites evidence of human habitation as early as 19,000 years ago. Mounds date back more than 2,000 years. Just before “contact,” at least five tribes occupied parts of West Virginia. Yet the earliest non-native explorers did not find large numbers of native people present. A likely possibility is that European diseases, against which natives had no immunity, arrived before their carriers, transmitted by the few natives who happened to meet the recent arrivals. In recent years, indigenous people, some affiliated with an inter-tribal tribe, have been outspoken about their presence. For present controversy, see “energy production,” especially fracking and wind turbines.

Dark skies get a shout: the Highlands’ combination of sparse population and high elevation makes it “the best place in the mid-Atlantic region to see a clear night sky.” For Watoga State Park, it’s official: in 2021, it was recognized by the International Dark-Sky Association as a Dark Sky Park. Bonus: every year there, from mid-May to late June, stars and meteors are eclipsed by a synchronous firefly display.

At Bear Heaven, a Forest Service recreation area on Stuart Memorial Drive east of Elkins, a small campground sits near a “jumble” of sandstone blocks. For years, our children and now our grandchildren have climbed all over and through its “labyrinth of narrow clefts.” We can confirm the caution (which is also an attraction) that “it is possible to get lost.”

Cliffs in general draw attention by contrast to the predominant forest cover. Seneca Rocks and the walls of the New River Gorge are icons familiar to tourists and rock climbers alike. Bare rock is largely protected from human-induced stresses—fire, logging, grazing, development—and its endurance contributes to biological diversity. What lives there? For starters, lichens, mosses, salamanders, the Flat Spired Three-Toothed Land Snail (an endangered species), and the Allegheny Woodrat, aka pack rat. Van Gundy goes into some detail about these “harmless, charming, and inquisitive animals.” Some colonies persist in the same location for many thousands of years; scientists have studied their middens for information on ecological conditions over the past 25,000 years.

Waterfalls are another iconic attraction, so much that our Department of Tourism has devised an app called the Waterfall Trail that will guide visitors to 40 of them around the state. But did you know about “lost waterfalls?” Water emerges as a spring, cascades down the surface of insoluble rock (usually sandstone) and sinks back into the ground where it finds a lower bed of limestone. See the magical photo, “A Lost Waterfall in Randolph County,” on page 91.Place names: Van Gundy enjoys curiosities, and finds a group along US 19 near Birch River. There are Nikola Tesla Road, Polemic Run, and on the other side of Powell Mountain, the village of Muddlety—almost too cute.

Cranesville Swamp is featured twice in highlighted side trips, from US 50 between I-79 and Gormania and from US 219 between I-68 and Elkins. The former describes a 28-mile jaunt along the Cheat River, up Briery Mountain to Terra Alta, and north again past Alpine Lake. The latter, a shorter departure from the designated route, takes the traveler through Maryland’s Swallow Falls State Park.

Cranesville is a Nature Conservancy preserve with a 1,500-foot-long boardwalk and other trails. Van Gundy informs us that it’s not technically a swamp, lacking trees in its open wetland area, but more properly a boreal bog or southern muskeg. Its location in a “frost pocket” surrounded by highlands keeps it cool year-round. Look for porcupines, northern water shrew, and Tamarack, as well as the insectivorous Sundew.

WV 72 gets the highlight treatment twice, befitting its split personality. North of Parsons, it’s the Cheat River Highway. Past US 50 (beginning the longer route to Cranesville), it hugs the Cheat for twelve miles, a park-like stretch with scattered turnouts for boaters, fishers, and travelers who don’t want it to go by too fast (the road or the river).

A contrasting piece of 72 turns off US 219 east of Parsons. It also follows a river, not the main stem of the Cheat but its Dry Fork (aka Black Fork below Hendricks, where the Blackwater enters). Van Gundy writes: “Route 72 . . . at first hangs precariously on the north side of the canyon of the Dry Fork River and then climbs onto what amounts to a dissected limestone plateau 400 to 600 feet above the valley. The many curves . . . are the result of its winding in and out of the numerous small stream valleys that have cut into the plateau surface.” This tortuous road offers access to the north trailhead of the Allegheny Highlands Trail, the south trailhead of the Blackwater Canyon Trail, and the south trailhead of the Otter Creek Trail. Beyond them, one can leave Rt. 72 on the River Road (CR 26), no wider but far more direct, and rejoin 72 closer to Canaan Valley.

Maps: You’ll find maps for highway segments, bird flyways, forest ownership, and many other topics sprinkled throughout the book. Best of Show is the brilliantly colored “Geologic Map from Elkins to Seneca Rocks,” which gains a full page in the new edition. It’s a work of art.

Down South: Two-thirds of the highway segments are in the northern section, but there’s plenty to see down south. Take US 219: it’s the one Highlands highway that goes border to border. As you approach Union, the paradoxically-named county seat of Monroe County, there’s a Confederate rifleman’s monument our kids called “the man out standing in his field.”

The hike, a mile and a half from Limestone Hill Road at the top of Peters Mountain, brings you to Hanging Rock Raptor Observatory in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests. It’s on the Continental Divide at 3,800 feet with an eye-level view of migrating hawks, eagles, and ospreys. You’ll see the most at the end of September.

What I wrote about the first edition is truer for the second: “This well-written guide will be equally useful to day-trippers and determined explorers, and even those of us lucky enough to live here will find there’s more to discover.”

The book will soon be available in WVHC’s online store. Watch The Highlands Voice and our social media for updates.